Your cart is currently empty!

A Soldier’s Heartbreak…the story of Virgil Goad

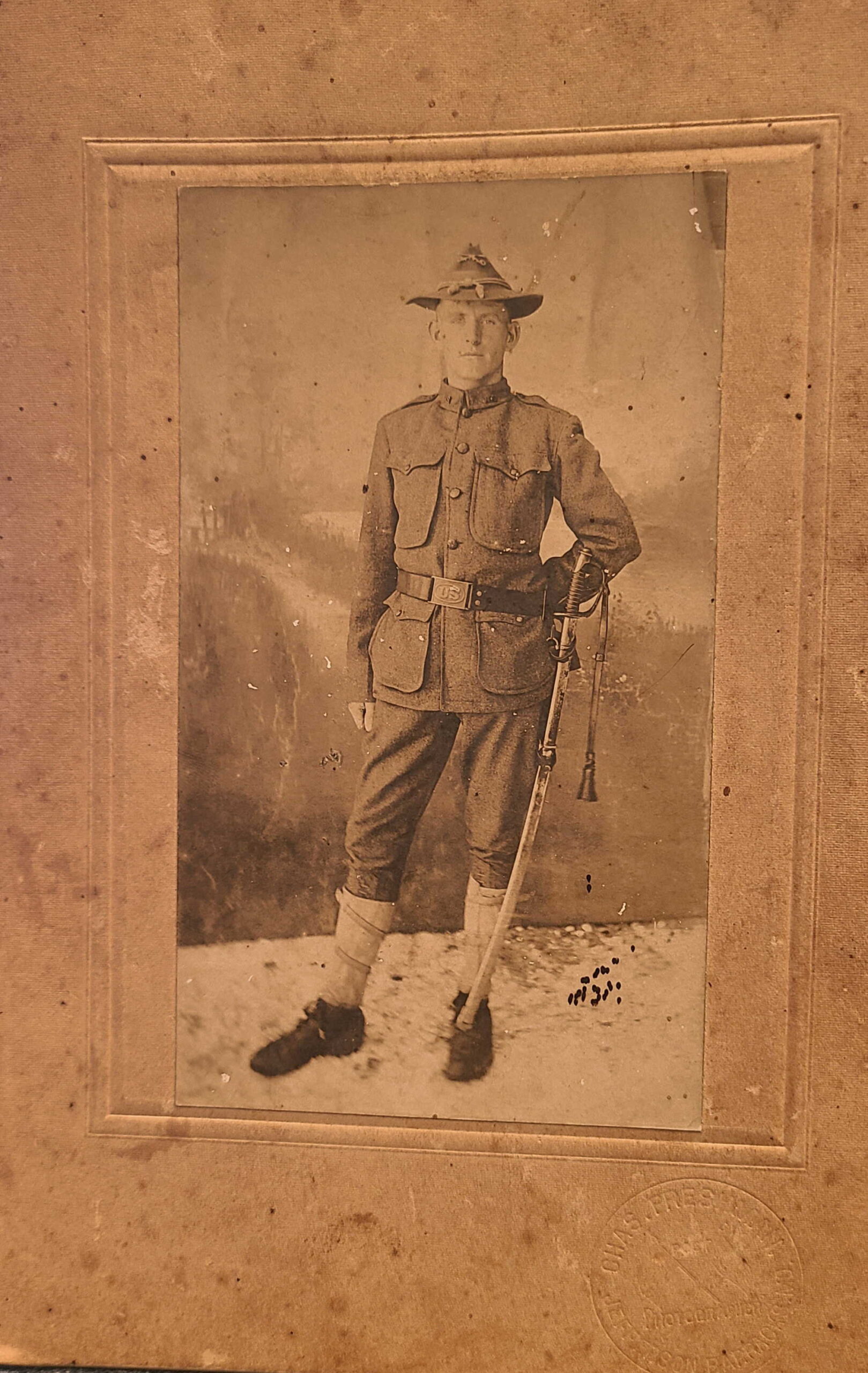

Virgil Goad joined the U.S. Army on a cold day in January, 1910. He soon found himself south of St. Louis on the banks of the mighty Mississippi River at Missouri’s Jefferson Barracks, the primary facility used by the army to train its soldiers. He enlisted for a term of three years and was identified as being 5 foot 7 inches in height and of fair complexion with blue eyes and dark brown hair. He was a farmer and, undoubtedly, the possibility of adventure in faraway places lured him away from the fields and back-breaking monotony of a Macon / Sumner County farm boy.

Over the next few years, Goad found himself enduring a different kind of monotony in the form of endless drill and military routine, occasionally punctuated with the adventure he had sought. During that time, he had also cultivated a relationship with his hometown sweetheart, Miss Vergie Davis. Vergie was the only child of John W. Davis and Annie Etta Rhodes. Virgil and Vergie had known each other before Virgil’s departure to the military and had courted from afar in the form of letters. Her parents gave their consent for marriage and, while Virgil was on leave, the young couple celebrated their marriage on June 9, 1915.

A scant two weeks later, Virgil left for a return to Jefferson Barracks and what would become a long dance with tragedy.

In his earlier enlistment, Virgil Goad had been a part of some of the action on the border with Mexico and had, in fact, been honorably discharged on May 30, 1915, only a few days before his wedding. In his first stint with the military, he had served as a private in Company H of the 21st Infantry Regiment. His reenlistment shortly after the wedding was a testament to his desire to get back into the action and he soon found himself returning to familiar territory, first, at Jefferson Barracks, and then rapidly back to the border.

Virgil Goad again found himself serving under General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing. The white dust of the desert frequently covered his uniform, causing he and his fellow soldiers under Pershing’s command to be referred to as “dobies”, short for “adobe”, the name of the sand-colored houses of the locals. After the incursion of Pancho Villa and his followers into Columbus, New Mexico, in March, 1916, the United States launched what has come to be called the Mexican Punitive Expedition and the adventurous Virgil Goad was smack in the middle of it.

On this jaunt deep into Mexican territory, the Westmoreland boy found himself witnessing some historic “firsts”: the US Army sent supplies for its soldiers into Mexico on Dodge trucks, and the First Aero Squadron flew reconnaissance flights overhead. Initially, these “firsts” were failures – the primitive trucks repeatedly broke down and the planes lacked the power to fly high enough to pass over the mountainous Mexican territory. Fortunately, better trucks and more powerful planes would eventually arrive. The video that follows, courtesy of Historic Films, offers a glimpse of the US soldiers involved in the conflict. It is possible that Virgil Goad is among those appearing in the video.

For Virgil Goad, the sight of these modern advances in warfare served to further his spirit of adventure. A young George S. Patton was also on the expedition, serving as a lieutenant on the staff of Gen. Pershing and closely observed the art of desert warfare. The Punitive Expedition was unsuccessful in that it did not result in the capture or death of Pancho Villa, however, it did prove successful with the battlefield training it provided to the U.S. Army and to the establishment of a well-earned reputation for Gen. Pershing. The Expedition officially ended on February 5, 1917. Virgil Goad returned as a Corporal, but with a grieving heart.

Back in Westmoreland, measles was sweeping through the community. For a lucky few, the disease was a minor annoyance, but for the majority of those afflicted, it brought prolonged days of agony. Like most, the disease was likely in Vergie Goad’s body several days before it first manifested itself in the form of a mild fever and cough. By the second day of symptoms, Vergie had grown more uncomfortable and her eyes became inflamed with an annoying form of conjunctivitis. Dr. T.Y. Carter began treating her on January 15, 1917 with the rash of small blotchy red spots progressively covering her body. As the days passed, Vergie’s condition worsened with her cough becoming more persistent. Her fever was a continuous 104 or higher, causing delirium, and her mother began to fret, as all good mothers do in such situations.

By the seventh day, or so, it was hoped by all that her symptoms would show improvement, as it often did for many patients. Instead, her condition worsened. A second doctor, Will Law joined in the treatment of Vergie who remained at her mother’s home. Neither prayers nor medicine could stop the progression of the disease. Her death certificate simply reads “measles” as the cause of death. The doctors did not state the dread complication that actually put Vergie in her untimely grave. It could have been dehydration from the persistent vomiting or diarrhea or high fever; bronchitis could have settled in her lungs leading to its kindred spirit, pneumonia. Regardless of the complication, Annie Rhoades Davis stood with a host of friends and relatives, and sobbed relentlessly as her only child was lowered into the earth at Pleasant Grove Cemetery the next day. A thousand miles away, a heartbroken Virgil Goad mourned the loss of his sweetheart in the dusty desert of northern Mexico.

A loss like that can do something to a man.

A broken heart caused Teddy Roosevelt to try ranching in the solitude of the Dakota Territory. Thomas Jefferson was despondent for years afterward, disappeared on long, solitary rides around his plantation, and never spoke of his wife again. Andrew Jackson blamed Rachel’s death on the malicious attacks to her character during his run for the presidency and sought retribution against his political enemies and perpetually mourned her loss for the rest of his life. And Virgil’s commanding general, John Pershing, whose wife and three daughters had burned to death in San Francisco, threw himself into his military calling, aging noticeably and growing evermore stern in his demeanor.

Virgil Goad chose to remain in the army. Perhaps haunted by the specter of her death in his absence, he seemed to have buried his sorrows in the routine of the soldier’s life. And when the US went to war in Europe, Virgil followed “Blackjack” John Pershing abroad, arriving in France in October, 1917 as a member of the 23rd Infantry, a part of the US Army’s Second Infantry Division, and a well-trained, battle-hardened veteran who now held the rank of Sergeant. The “dobies” under Pershing in Mexico had now become the “doughboys” in France.

In Westmoreland, as in other areas of the county, flags were hung in churches with blue stars sewn onto them indicating the number of church members serving. One of the 19 stars on the flag in the Westmoreland Methodist Church represented Virgil Goad.

Virgil was among the soldiers who fought the Germans to a standstill at Chateau-Thierry on June 2, 1918, having only a few hours worth of fitful sleep in a 72-hour span of time. This crucial battle stopped the German offensive from taking Paris and was the first action in Europe for Virgil and the 23rd Infantry. On June 15, Virgil suffered the terrifying fate of many a soldier in WWI; his gas mask served as some protection for his lungs, but the mustard gas he encountered that day seared some of his exposed flesh, leaving scars that would never go away. This event briefly took him off the front lines but by the 20th, Sgt. Goad was back in the fray, this time at Belleau Wood and Vaux. Both ended in bloody victories for the 23rd Infantry and the entire command, including Virgil, were awarded the French Croix de Guerre for their collective bravery during the two week battle.

And then he was at Chateau-Thierry again, and then in the beet fields at Soissons and other towns, rivers and forks in the road that are collectively known as the Second Battle of the Marne which drew to an end on August 2, 1918. It was likely about this same time that Virgil may have received word of the unexpected death of his mother, Rora Etta Goad, due to complications from surgery to remove her gallbladder.

In mid-September, Virgil Goad was with the 2nd Division at St. Mihiel, the first time the Americans were under the exclusive command of General Pershing and the comparatively easy victory there that led to the collective nightmare of the Meuse-Argonne. From the morning of September 26, 1918 until the first day of October, the fighting there was relentless and brutal, and it was only the beginning. Both day and night the artillery shells rained down and burst among the troops; the spatter of machine gun fire mowed down legions of men dodging clouds of gas as they clawed and cut their way through unending mazes of barbed-wire. The screams of wounded and terrified horses served to punctuate the never-ending wail of the wounded men and the terrified shrieks of those witnessing clouds of gas oozing across the fields in their direction. The mere feeling of the gas mask, strapped tight against the face, was claustrophobic in its confinement, but when combined with the fierceness of battle and the rush of adrenaline and its accompanying rapid breathing and heartrate, and the myopic view through the grotesque eye holes, the feeling of physical and emotional suffocation was nearly unbearable. A promised respite on October 1st instead turned into a fierce battle for Blanc Mont Ridge, fought on a plain that turned into a bog of water, mud, blood and body parts earning Virgil Goad’s 2nd Division, the “Indianhead Division”, the title of the bloodiest division of the American Expeditionary Force. The footage that follows offers a glimpse of what Virgil Goad experienced:

The battles in and around the Argonne Forest would continue until near the end, which would come on the 11th day of the 11 month, Armistice Day.

Jubilant celebrations became the order of the days that followed and the surviving soldiers began to have dreams of returning home while their families back home sang praises for their survival. But hopes for quick reunions soon faded with the reality that transporting the vast American Army back across the Atlantic would be a slow, tedious process, and that many soldiers had to remain in Europe as a victorious army of occupation. The early days of hope turned into many months of waiting, but when the time arrived, the reunions were celebrated with tears of joy.

For those who served, time often did not allow them to forget the horror of it all. Certain sounds would rekindle memory of an experience: the pop of a firecracker, an unexpected firing of a gun, the dropping of a book, the scream of a horse in distress. Flashes of lightning in a terrific nighttime thunderstorm were found to be particularly unnerving. Even the mundane act of stepping onto a muddy street could trigger memories of a shocking episode witnessed by the former soldier. Gallatin’s physician who served, Dr. Bill Lackey, observed, and underlined the last eleven words for emphasis, the following that could be said for all:

If the people of the U.S. knew what our boys have endured they would not believe it…strong men have learned to cry over here and be unashamed.

For Virgil Goad, death also came as a result of the Great War. But, for Virgil, his death did not come at the end of a bullet, or sudden burst of an artillery shell, nor did it come from a lethal gas canister or onset of disease. Instead, for Virgil Goad, death was at the hands of murky shadows within his own mind – shadows that would inexorably haunt the man to death.

Virgil Goad left Europe on February 23, 1919. He was onboard the USS Mongolia troop transport ship, pictured below at port in New York in 1918:

Virgil Goad appeared on the ship’s manifest as passenger #914, a part of the “sick and wounded” section. The manifest stated that Goad was “Psychosis Manic Dep”. It is likely that he had been a patient at the convalescent camp of the military hospital at Savenay, France prior to his departure to America from St. Nazaire, France on the Mongolia. The ship dropped anchor in Hoboken, New Jersey on March 7, 1919 whereupon Goad was admitted to the Greenhut Hospital on New York City’s Sixth Avenue. It is not known how long Virgil was a patient at Greenhut but his record indicates that he was admitted to Central State’s Hospital for the Insane in Nashville on September 12, 1919. The Census of 1920 records him as still being a patient there.

On January 16, 1921, Virgil Goad was transferred to Augusta, Georgia where he became a patient at the United States Veterans Hospital #62. It was there, 424 miles away from his family in Westmoreland, that his torturous journey came to a lonely end at 12:10 am on May 14, 1923. His cause of death was recorded as “cerebral hemorrhage” with “general paralysis, cerebral type” being listed as a contributory cause. “General paralysis, cerebral type” was, in 1920s medicine jargon, a diagnosis of insanity. The cause could be many things, including untreated syphilis. But, it should also be noted the military at the time frowned on soldiers suffering debilitation as a result of what later was termed “shell shock” and still later post traumatic stress syndrome or PTSD, and little official recognition was given by the government. In her extraordinary book Sumner County in the Great War: Let Us Remember, Judith Morgan simply stated of Virgil Goad, “somewhere along the way, in one battle or another, he cracked.”

Virgil’s father, Wade James Goad, would spend a significant portion of the rest of his life pleading with the US government to honor his son’s death with the awarding of a pension to his next of kin. The elder Goad took the train to Nashville to the Stahlman Building and the offices of Creasy and Creasy, the law firm of Westmoreland brothers where Floyd Creasy was a partner and the attorney who would first represent Mr. Goad in his efforts. The letter appearing below contained the terse reply from the VA:

Realizing the government’s penchant for weaseling its way out of providing pensions to the next of kin, the decision was promptly appealed and again denied on March 5, 1935. Declining health forced the father to eventually give up trying to persuade the government to admit military service played a role in the untimely death of his son. In the government’s opinion, Virgil Goad’s shell shock and resulting insanity was not caused by his service to his country in the Great War.

One last indignity haunts Virgil H. Goad still today.

When he died alone in the hospital ward in Augusta, Georgia, his body was placed in a wooden casket, loaded onto a train and eventually made its way to Westmoreland’s L&N depot. No heroic welcome awaited him. A forlorn father and members of his family soon accompanied his casket to Pleasant Grove Cemetery where he was laid to rest beside his sweetheart, Vergie. The burial site of Vergie Davis Goad is marked with a large stone picturing an angel standing at the gates of Heaven bearing the inscription:

She was the sunshine of our home,

She’s now a treasure in Heaven,

To beckon us all to a higher life,

We will ever cherish thy memory till we see thy heavenly face.

But, sadly, no marker proclaims the existence of Virgil Goad. Instead, only the faintest hint of a depression in the earth offers the sense that a body is at rest there.

Recently, Will Troutt, a US History teacher at Westmoreland High School, and Glenda Akin, the retired librarian at the school, along with a group of WHS students from the Honors US History class of James Ward approached me in an effort to correct what they perceived to be an injustice to an individual who had served this country. A government headstone has been ordered to mark the site of Virgil Goad’s resting place at Pleasant Grove. Though the monument itself is free, the proper setting of the stone is costly. If you are a reader and wish to make a donation in remembrance of this forgotten soldier of the past, you may send a check to the following address:

Pleasant Grove Cemetery Association

PO Box 872

Westmoreland, TN 37186

(Note “Virgil Goad Fund” in the purpose of the check and payment should be made payable to the Pleasant Grove Cemetery Association)

To “read more about it”, check out the following:

Sumner County in the Great War: Let Us Remember by Judith Morgan (publisher Sumner County Historical Society, January 2017)

12 responses to “A Soldier’s Heartbreak…the story of Virgil Goad”

Another interesting story, Mr. Creasy! Lots of fascinating angles.

Thank you and thanks for reading, Jeff!

Wow! What a great story. Thank you.

Thank you, Jean, for reading this!

Amanda please thank you for bringing attention to the life and sad death of my great uncle! Very well written!

Thank you for reading and a big thank you for the information you provided to me in writing his story!

Thank you for this story and the history of one great American from our little town Westmoreland. I have sat and listened to many stories from my grandparents and mom and her sisters and brother. I wish I had recorded these to replay for my kids and grands. I try and hand down some of these stories when I can. So happy,John, that you are doing this. Jan May Kepley Gray.

Thank you! I hope you continue to enjoy future stories, as well.

John, is this in print somewhere. Pat said he would like a copy.

I only have it posted online, but I can make a copy of it for Pat. Thank you for reading!

He said he would appreciate it. Be glad to pay whatever the cost.

I really enjoy reading these, John. Keep up the good work.

Another interesting article, Mr. Creasy. Thanks for sharing!